A Musical Mystery? Crack an old Postcard Code

Shorthand and use of non-English languages reduced the number of people who might read a given post card. Nevertheless, senders still ran the risk of postal workers and others (family members, friends, neighbors) being able to read the cards. Perhaps more the case with non-English languages sent from or delivered to ethnic and/or diverse neighborhoods, but more people may have been able to read shorthand then than now.

And then there are codes. It will likely come as no surprise that some people used codes to communicate through postcards. With codes, the recipient had to have the key to decipher the message–but codes likely defeated casual readers.

As a matter of fact, I have a postcard written in code that has, so far, defeated me.

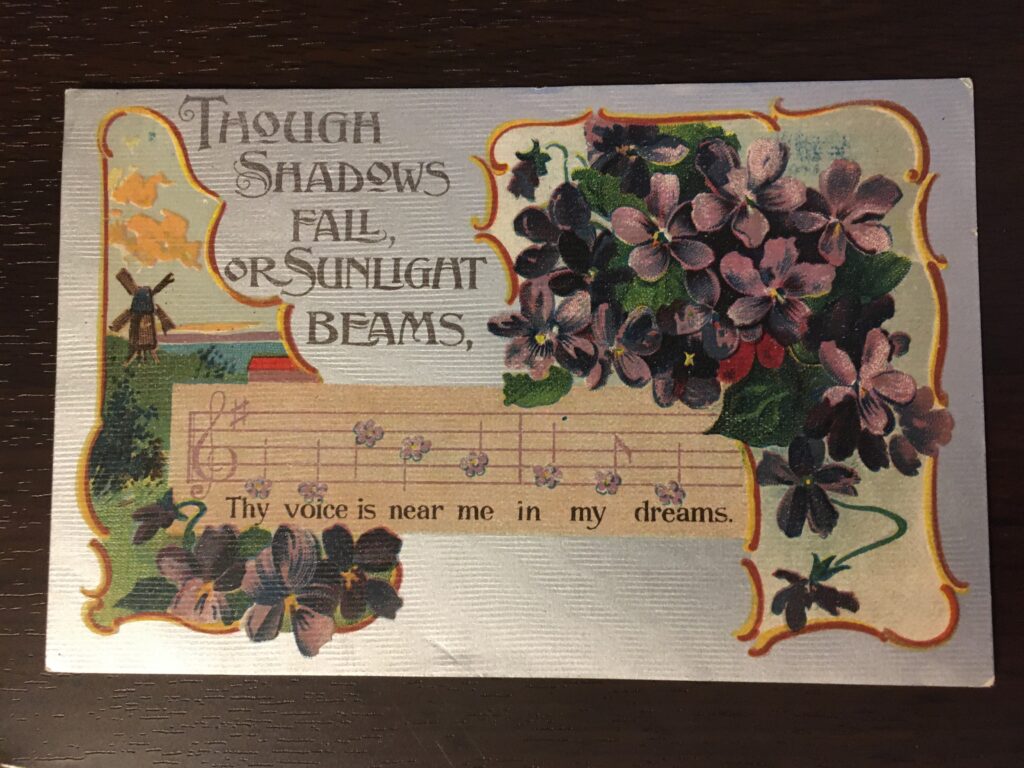

From the image side, it appears unassuming. Rather pretty, even, with its combination of flowers and music. I’m not sure exactly which song the lines are from (that’s an area for future research). It was printed in Germany; this is fairly typical of the first decade or so of American postcards. As suggested by the light on the silver-colored backing, this is a glossy postcard to a degree. The paper also has minute ridges, which is more visible on the reverse.

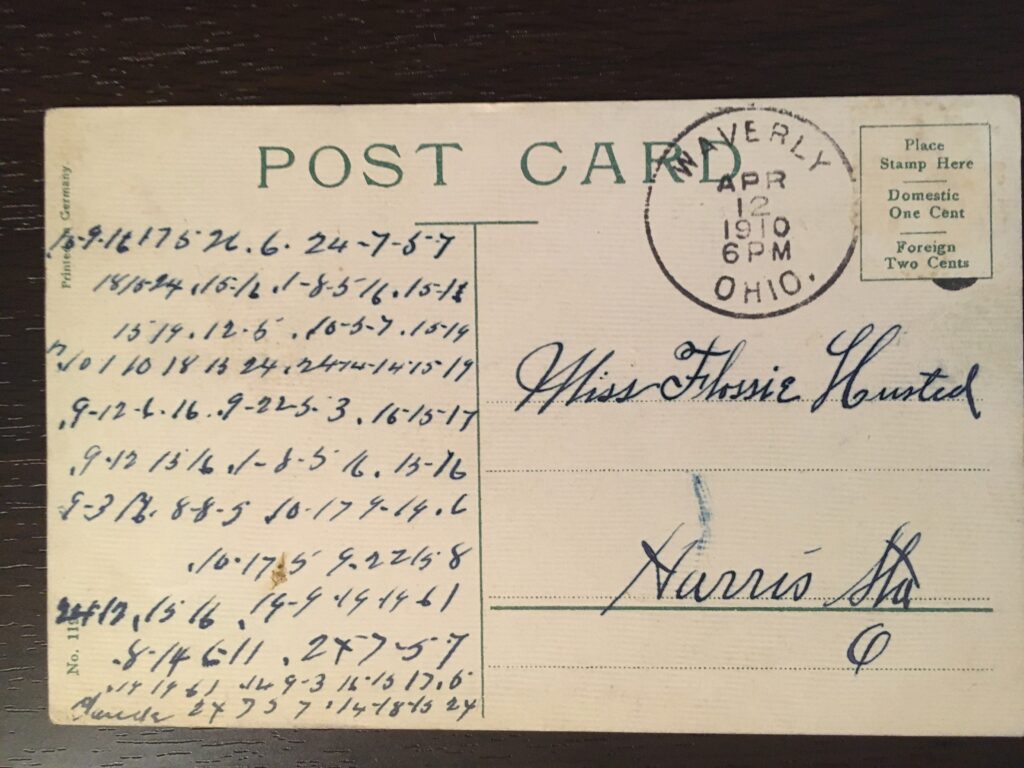

The recipient was one Miss Flossie Husted. Her address, according to the postcard, was likely Harris Station Road in Waverly, Ohio. A search for Flossie Husted in the 1910 Census resulted in only one in Ohio, who lived in Twin, Ross County, only about 10 miles away. There was a Florence Husted up in Toledo, Ohio, and other Florence Husteds outside the state. Since the card is postmarked 1910, the closest is likely the right Flossie. Since the card was sent to her in Waverly in April and the Census placed her in Twin in April, she may have worked in Waverly during the week and gone home on the weekends.

Moreover, the Flossie Husted listed in the Census was a nineteen year old white woman, living with her parents (her father was a farmer). She already had an occupation–teacher–and an industry–music. If she was the intended addressee, then the musical element of the card may not have been accidental. (Though that could be the case with many others, too, so it’s hardly diagnostic).

Someone, as yet unknown although the sole element of the message that’s not in code could be Frank, sent Flossie a coded message. This may be a simple substitution of numbers for letters as the highest number appears to be 22, but the actual assignment of numbers-to-letters defeated my initial assays at deciphering it. Do the dots and dashes matter? if so, what do they donate? I’m not a natural code-breaker, so I’ve basically set this aside for now with plans to come back and try to crack it at a later date. (Of course, if someone managed to crack the code before then, I wouldn’t mind a bit!)

One possibility that occurs to me is that a periodical or newspaper of the day may have featured an article about codes and included a sample code or instructions for making one, that the sender used and counted on Flossie having at hand. Alternatively, there may be a musical element to the code. Since the card was postmarked in Waverly and sent to Flossie in Waverly, odds are it was sent by someone locally.

Failing a code or obscure language or form of writing, there’s a stand-by alternative available to this day to almost anyone who wants to keep prying eyes from reading a message: use really bad (i.e. virtually illegible) handwriting–but then one risks the recipient, too, being unable to figure out what the sender means.

“A Musical Mystery? Crack an Old Postcard Code,” copyright 2021, A.R. Henle.

4 Comments

Pingback:

ShadowWolf

I wasn’t quick enough to solve the cipher, but there are tools online that could help with the majority of these. For number ciphers, I suggest converting them directly to letters if possible. Then, if there is enough text, there are any number of auto solvers available. This assumes that the cipher is a standard mono-alphabetic substitution cipher (MASC).

There wasn’t a lot of published material on ciphers such as this in 1910. The first major English text book was written by Parker Hitt, copyrighted in 1916 and likely published the same year. These days it is a free download either from the Friedman collection or Google Books. You can also download the army field manual FM34-40-2. Some of the texts in the Friedman collection such as the cryptanalysis series might also help, but the language is a bit tough to read.

The music is probably just an artistic device to imply a song. In any case, the key is G#. A Goole search just turns up a blank post card of the same kind. The time appears to be 5/4. The first measure has 5 quarter notes. Then the following set of notes are incomplete. It is odd that the key is shown but little else. The verse appears to just be the normal stuff for post cards. A Google search just turns up ablank post card that is the same as this one.

admin

Armin Krauss, a blog reader of Klaus Schmeh solved this. You can check the comment trail on the pingback above or: here’s what he found (which I don’t blame him for coding–perhaps it’s my modern sentiments, but it roused a chuckle in me)

Baby I wanted

to talk to you

so bad Am so

sorry you did

not have time

to talk to me

I sent all the

love and

kisses to my

baby girl

another kiss

your baby

Pingback: