Typewritten Irregularities: Filling a Postcard in Type

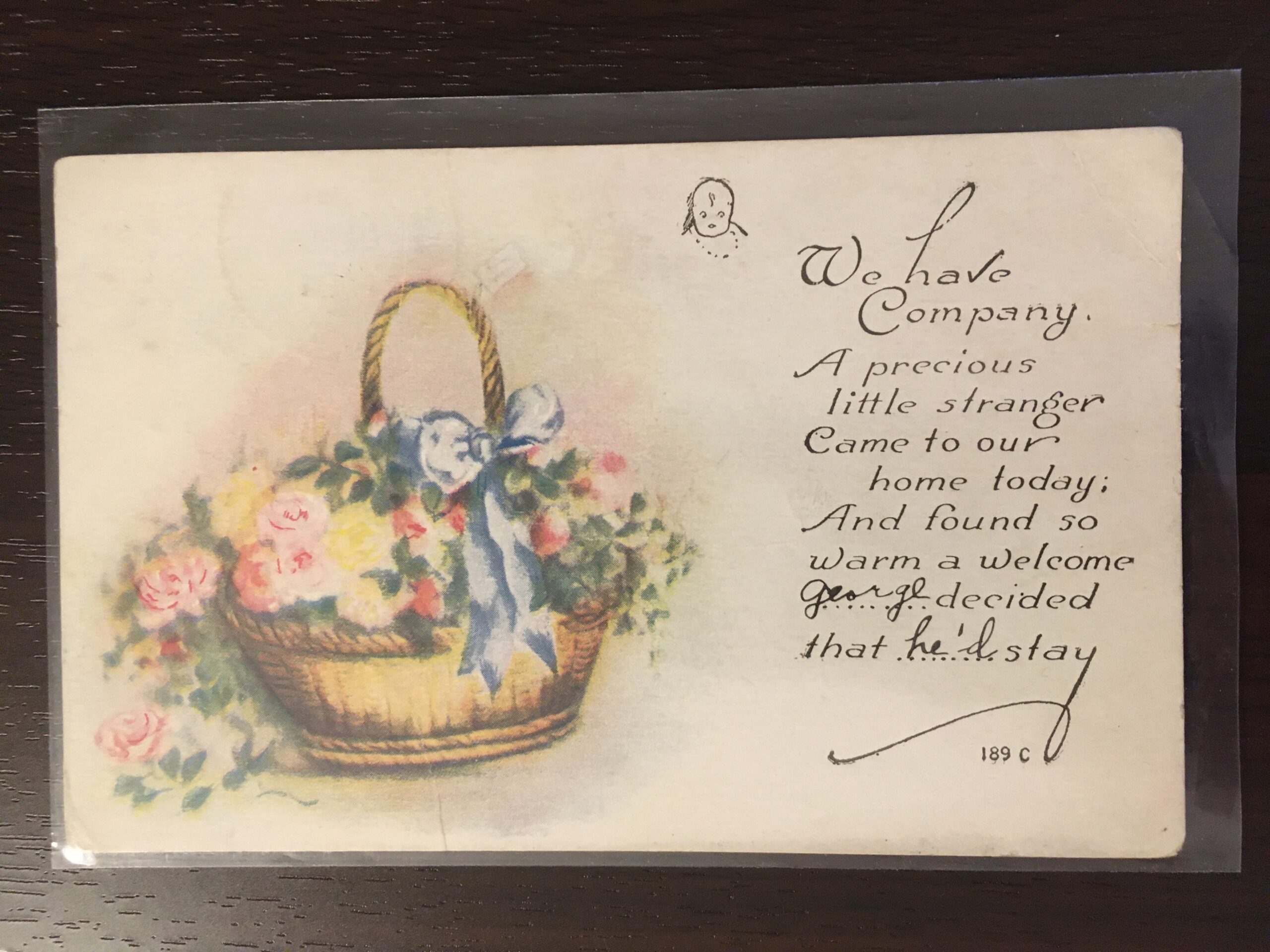

If you sat down to write a postcard and send it, how would you fill the space. With a pencil? Ink pen? Marker? Crayon? How about typing? True, in the modern world we can design postcards and have them printed, but this wasn’t an option at the turn of the twentieth century. The vast majority of postcards that I’ve seen have handwritten messages, in pencil or ink, sometimes crayon. (As an aside, my personal preference is ink pen because pencil messages can be a pain to decipher.) There are some with pre-printed messages or blank forms (I’ll share some here sooner or later) and others with stamped messages, as in the previous example.

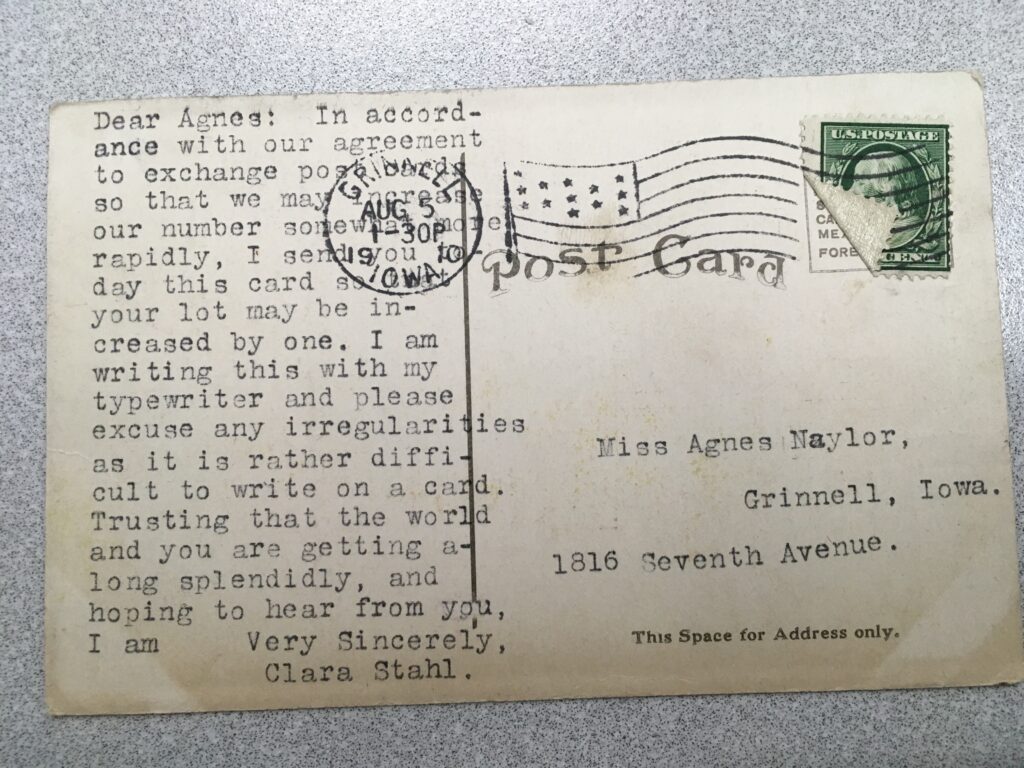

Then there are the typewritten cards. These aren’t unique by a long shot. I have a fair number. That said, most of those contain short messages. Occasionally, however, someone tries to use just about every inch of space. This works a lot better with pen or pencil (there will be a lot of these shared here over 2021) than with a typewriter. Nevertheless, here follows an example.

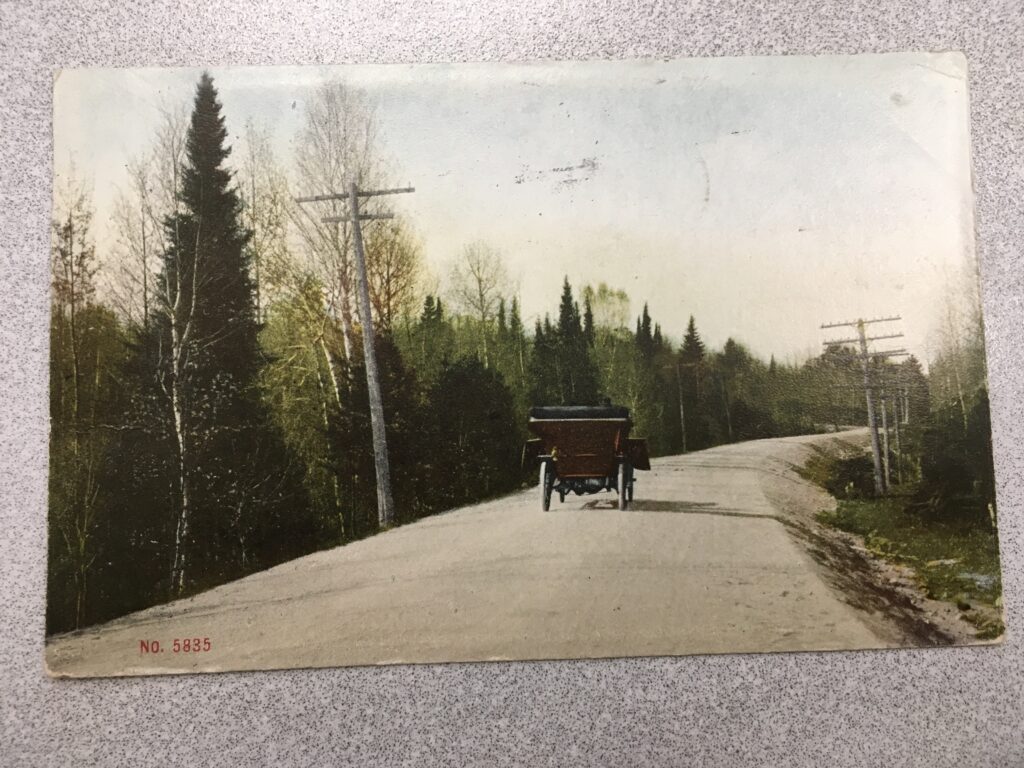

We’ll start with the image side. The card bears nothing on it to indicate the maker, not an uncommon occurrence for a visual such as this. It’s essentially a colorized photo, probably ordered by a local photographer, stationer, or drug store from a printer. The number in the bottom left likely refers to this image’s place in the printer’s production line (the 5,835th image). It portrays a local scene with evidence of progress: telephone or electricity lines, an automobile, and a deliberately constructed road.

My guess–and this is only a guess–is that Clara Stahl may have selected this card to type out a message in no small part because it is a simple, local scene. She was likely skilled at typing, for she worked as a stenographer in a legal office in Grinnell, Iowa. Yet even a skilled typist might need a little time to work out how best to align a postcard in a typewriter. Or not. She might have had experience doing the same with legal forms and notecards. Whether or not she actually had trouble (the typing looks pretty good to me), she asked her correspondent to “please excuse any irregularities as it is rather difficult to write on a card.”

Clara was also in her early twenties at the time, and living at home. She was born in Iowa, but both of her parents emigrated from Germany. Her father was a plumber, and her parents rented rather than owned the house they occupied. Clara’s acquaintance with her correspondence, Agnes Naylor, likely arose from school. They were roughly of an age, and both from Grinnell.

And both evidently postcard collectors. The first decade of the twentieth century in particular was an era of postcard collecting. It was a golden era in many ways–but as with many golden eras contained the seeds of its own destruction. Rather than recount the history here, there’s a solid summation available from Alan Petrulis’ MetroPostcard.com.

Agnes Naylor and her sisters happen to be the reason I got hooked on collecting old postcards sent to the same person or family. I stopped off at an antique store in Bethlehem, New Hampshire, a year and a half ago, after a trip up Mount Washington, and wound up sifting through a pile of unsorted postcards. I looked at the inscription side rather than the images (for reasons to complicated to explain here) and was struck by how many were sent to Agnes Naylor or another Naylor. My guess is the proprietor of the store (who was off on vacation; I dealt with his assistant) had recently acquired some postcard albums and disassembled them for their component cards. I’m sure I missed some Naylor cards (and others, for I picked up two other, smaller, sets that same day) but I wound up paying for a batch of 200 cards sent to one or another Naylor, 150 of them to Agnes.

Agnes Naylor was the youngest of four sisters and two brothers. As with her friend Clara, she worked as a legal stenographer. She grew up in Grinnell, and attended Grinnell College for a few years although she may not have graduated. Her father was a farmer when she was born, a day laborer at the turn of the century, and a laborer at Grinnell in 1910.

In addition to both collecting postcards, Clara and Agnes had an agreement to send each other postcards to increase their collections. This was part of the logic underlying post card clubs, whose organizers helped connect collectors in different parts of the nation. Many members of postcard clubs were particularly interested in gathering specific types of postcards (photographs of places were sometimes preferred over holiday cards, for instance). Since Agnes and Clara both lived in Grinnell, they had more limited options–but each might also travel elsewhere; some of the 150 cards sent to Agnes that survive were addressed to her in Des Moines rather than Grinnell. Also, sometimes collectors had connections (friends, family, or club members) in other cities who sent them blank cards which they could then use for exchanges.

The mail was quite efficient at the time, and it’s possible Clara dropped the card in and expected her friend to receive it that same day. One of the appeals of postcards was the low cost of sending them–but a drawback that anyone who handled the card could conceivably read the contents. Therefore anything entrusted needed to be something the sender, at least, didn’t mind becoming public knowledge. In this case, the typewriting made the card even more legible for all hands through whom it passed.

Clara made different choices with some other cards, but that’s a tale for the next post.

“Typewritten Irregularities: Filling a Postcard in Type,” copyright 2021, A.R. Henle.